Back in my day, the word “theory” meant something. So, in all my attempts to learn music theory, I was stymied by suggestions of memorizing seemingly unrelated collections of patterns, facts, and rediculous nomenclature. With dedication, books, wiki pages, and a good instructor (Ed Dee of Corvallis), though, I was able to make some progress. To help, I wrote a little program for exploring scales, notes, chords, and temperament.

Downloads

MusicWheel was build with processing.org. You can play with it by downloading one of the following (about 7 megabytes each):

(Note: On OSX, if you get an error about the application being “damaged,” try going to System Preferences -> Security & Privacy -> Open.)

Info

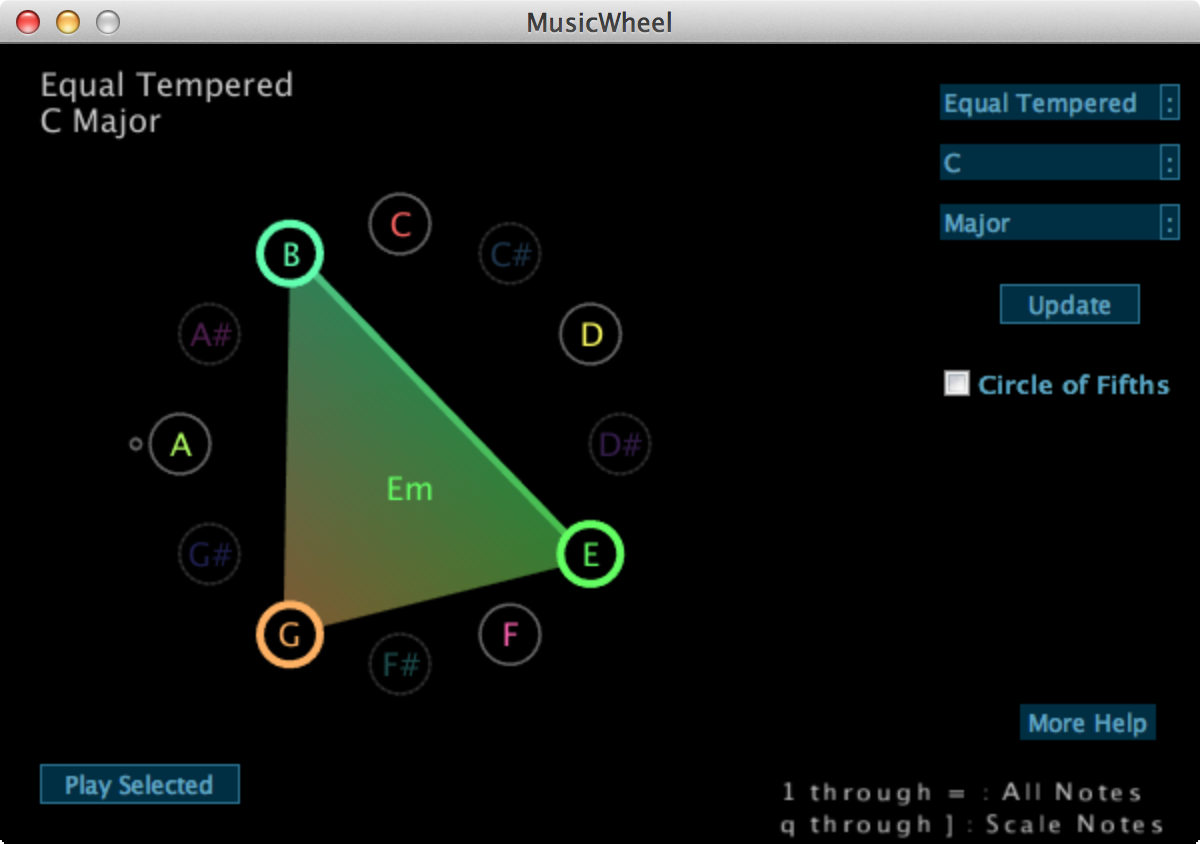

Use keyboard keys 1 through = to play any of the 12 notes; use q through ] to play only those highlighted in the current scale. Playing a chord shows it (if it’s major, minor, or one of the 7ths; e.g. try q+e+t keys simultaneously). Since most computer keyboards don’t support many simultaneous key presses, you can also click on notes with your mouse, and then click “Play Selected” to play them simultaneously. To change the instrument or scale, set the desired scale and click the “Update” button. If you play a C augmented chord, you can “unlock” a neat sound visualization. Play C# augmented to turn it back off again.

Currently this visualization only contains twelve distinct notes within a single octave.

Notes are colored according to the relationships of fifths (a note and its “fifth” of ~1.5x the frequency–give or take an octave–producing a particularly pleasing sound). Note locations can be arranged by fifths to produce the “circle of fifths.” Colored lines are drawn between notes and fifths when played. In the current scale, the relative scale (either major or minor) is annotated with a small circle. You can hold chords while changing between the chromatic layout and the circle of fifths layout.

The instrument dropdown allows you to play with different temperaments - nearly all modern instruments are in equal temperament, but historically a variety of temperaments (adjustments of tuning relating to the mathematics behind the fact that fifth [1.5x] relationships and octave [2x] relationships don’t play nicely together) were used. Since it’s not very often we see non-equally tempered instruments today, and even if you do find one you’ll probably need to be able to play piano, I thought this was a fun addition.

Cool things to notice:

The number of fifths that are contained within the different scale types. When playing multiple simultaneous chords, you can see how they share notes: for example a C major chord (C, E, G) and an A-minor (A, C, E) share two notes, and all four together make Am7. Similarly, a chord like Daug has three names: Daug (D, F#, A#), F#aug (F#, A#, D) and A#aug (A#, D, F#).

Scales share notes as well: try changing from C major to A minor (the note indicated as the relative in C major) - they contain all the same notes, only the pattern starts on the A rather than the C! This also illustrates a relationship between common “substitution” chords, particularly given just the gamut of 12 notes in a single octave - in C major, try playing a scale of chords starting at C (keyboard keys q,e,t; then w,r,y; then e,t,u, and so on); Dm and F sound similar, as they use many of the same notes. We can also compare the changes between major and major pentatonic, minor and minor pentatonic, and minor pentatonic and blues scales.

Equal temperament gives each scale within a scale type and each chord within a chord type a similar “flavor” or “color,” while other temperaments tweak the tuning of notes to give chords (and hence different keys) different frequency ratios. These adjustments in frequency ratios results in differing levels of harmony for various chords, resulting in each scale having a different “color”.* For a dramatic example, compare C major to E major for the different temperaments. In pythagorean, there is a single pair of fifths badly out of tune (known as a “wolf interval,” the amount of out-of-tuneness called the pythagorean comma), which you can probably find. In some temperaments, some scales are thought to some to sound “boring” (perhaps all chords are too harmonious) or “angry” (perhaps some are quite harmonious while some are quite inharmonious) or just “bad” (all chords too inharmonious). Due to the nature of octave (2x) and fifth (1.5x) ratios never quite lining up, even equal temperament contains some amount of inharmony: this inharmony is simply equal across scale and chord types. Some consider this a pitfall of equal temperament resulting in lack of musical expression, and lament its dominance in modern music–see, e.g., “How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and Why You Should Care)” by Ross Duffin.

*In equal temperament, a chord progression in a key type (say, C to Dm to Em in C major) sounds similar to the same chord progression in another key of the same type (G, Am, Bm in G major) because the relative ratios of chord notes are equal. Similarly with chord types: the ratios of C-to-E-to-G in the C major chord are the same ratios as G-to-B-to-D in the G major chord (give or take some octaves).